Breaking Models

Strategic Power and Joy in Perspective Resets

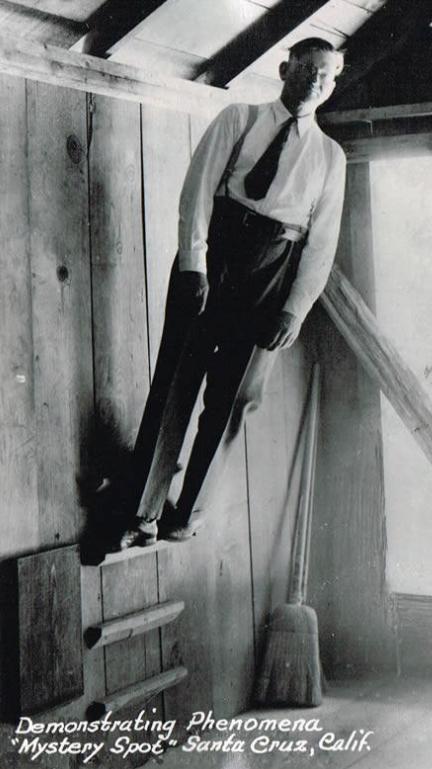

Approximately seven miles southeast of my house in the Santa Cruz mountains is a tourist attraction that has stood the test of time. For over eighty years, the Mystery Spot has enticed visitors with the promise of a mind-blowing proposition: experiencing a space where the established laws of physics do not quite apply. Gravity appears to malfunction, inviting us to imagine that the world might just be a little more interesting than we’d thought.

In the last few years, the physics community has quietly been confronting the possibility that the entire universe is a type of Mystery Spot with regards to the Standard Model of physics.

It started as a few isolated cracks. The Muon g-2 experiments at Fermilab confirmed that muons wobble significantly more in magnetic fields than the Standard Model allows.

We are now enjoying the Hubble Tension, an unresolved discrepancy in the expansion rate of the universe, depending on whether you’re looking at the early universe or the modern one. Even more fun, data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) suggests that Dark Energy — the mysterious force accelerating cosmic expansion — may not be a constant force at all, but one that evolves over time.

Optimism of Broken Laws

This type of mystery is what makes science exciting. (Consider the alternate story: “Scientists confirm the universe behaves exactly as predicted.” — hardly inspiring to the imagination.) The laws of physics, even more than the laws of humans, limit what we can do. We’re constrained by rules of the universe, and as we attempt to engineer our way into the future, we fight against these walls. Science fiction often explores potential realities that could be engineered if one or more rules of the universe (commonly gravity or special relativity) could be ignored. We want our understanding of the world to be wrong. We want our minds to be blown with unexpected, new views of our constraints.

Dreamers and revolutionaries will always hope that the Standard Model — our most useful map of reality—isn't just missing a piece. It’s structurally unsound, so perhaps anything is possible.

The story of physics over the last several centuries mirrors economist George Box’s well-worn observation: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” The most famous case of this may be Einstein’s work convincingly pointing to the incompleteness of Newton’s laws in specific contexts. It’s anticipated that Einstein’s General Relativity is insufficient in more extreme regimes, such as accurately describing the operation of black holes.

Of course, as Box indicated, Newton’s and Einstein’s models are and will still be incredibly useful. Models are one of the greatest tools we have for reducing work and taking shortcuts to understanding. A pretty good model of how a complex system works can save time and effort that add up to far more value than that model’s shortcomings subtract.

The brain is an amazing model-making machine. Mental models that we create subconsciously are information reduction tools and computational shortcuts. Young children create very accurate models of ballistic physics in their heads, allowing them without much effort to position themselves at the optimal place to catch a baseball. We are also amazingly adept at building mental models of people, organizations, economic systems, and ourselves. Many of these models are useful. And, of course, they’re all wrong.

Risks of Systemic Model Drift

Building the future of technology and society requires that we work in complex interconnected scientific, human, and economic systems. The scope and complexity of these domains is far beyond what we can contain in our brains, so we need shortcuts. Nearly every consideration, from techno-economic analyses to environmental impact mapping to ethical risk of a new technology, requires multiple approximations, simplifications and aggregations to reduce it to tractable scale. This is also where some of the greatest risks appear. The inaccuracies of a collection of technical and mental models duct-taped together to help us assess an opportunity might approximately average themselves out. However, it’s easy to incorporate the same type of shortcut multiple times, plus incorporate some unconscious biases, and end up with a system view that is terribly inaccurate. A classic case of this: consistently underestimating times and costs for completing an engineering project of any type.

At Applied Emergence,

we’re intrigued by situations where established models – what we think we know – fail to explain real-world outcomes. Whether assessing a deep-tech investment or debugging a stalled team, the first step is often digging in to understand what smart and useful but incomplete models people are leaning on, and how those differ from reality. In exploring these situations, we may employ tools like Agent Based Simulations to explore the causality and structure of these assumptions. Additionally, taking appropriate time to explore and learn the breadth of people’s views on the situation can ground these. This two-pronged approach can reveal where internal maps deviate from external reality, allowing us to de-risk decisions and uncover paths that conventional thinking misses.

An Example

Sometimes, multiple model resets are needed to land on a breakthrough path. At Google X, I led the Rapid Eval team, a collective responsible for creating the portfolio of new projects of the company. In that role, I had the privilege of collaborating with Kathryn Zealand and others in a pair of linked perspective shifts in wearable technology. The first shift was from actuator-first to control-first thinking (an analogy to anti-lock brakes or dynamic stability control in an automobile), and second, a shift from “wearable robotics” to “powered clothing.” Kathryn built the project and carried it forward to become the independent company Skip (skipwithjoy.com), a pioneer in a new category. Software and softwear FTW.

Hoping We Are Wrong

For me, that sort of perspective shift, representing a new understanding of a constraint, sparks joy. I want the models to be wrong so we can push boundaries and end up in new places. I hope that new physics rising from a wounded Standard Model will eventually lead to unexpected new engineering capabilities.

If we keep digging in, questioning our assumptions and breaking inherited understanding and our own models, we’ll land with new insight and a new plan. Perhaps something magical, that will survive the test of time. Like the Mystery Spot.